30 Years Ago: The STS-58 Spacelab Life Sciences-2 Mission

On Oct. 18, 1993, space shuttle Columbia lifted off in support of the STS-58 Spacelab Life Sciences 2 (SLS-2) mission to conduct cutting edge research on physiological adaptation to spaceflight. The seven-member crew of STS-58 consisted of Commander John E. Blaha, Pilot Richard A. Searfoss, Payload Commander Dr. M. Rhea Seddon, Mission Specialists William S. McArthur, Dr. David A. Wolf, and Shannon M. Lucid, and Payload Specialist Dr. Martin J. Fettman, the first veterinarian in space. Dr. Jay C. Buckey and Laurence R. Young served as alternate payload specialists. During the second dedicated life sciences shuttle mission, they conducted 14 experiments to study the cardiovascular, pulmonary, regulatory, neurovestibular, and musculoskeletal systems to provide a better understanding of physiological responses to spaceflight. The 14-day mission ended on Nov. 1, the longest shuttle flight up to that time.

Left: STS-58 astronauts David A. Wolf, seated left, Shannon M. Lucid, M. Rhea Seddon, and Richard A. Searfoss; John E. Blaha, standing left, William S. McArthur, and Martin J. Fettman. Middle: The STS-58 crew patch. Right: The Spacelab Life Sciences 2 mission patch.

As its name implies, SLS-2 was the second space shuttle mission dedicated to conducting life sciences research. Because of an oversubscription in the original Spacelab-4 mission, managers decided to split the research flight into two missions to optimize the science return for the principal investigators. The nine-day SLS-1 mission flew in June 1991, its seven-member crew conducting nine life science experiments. Because of her experience as a mission specialist on SLS-1, managers named Seddon as the payload commander for SLS-2. Eight of the 14 experiments used the astronauts as test subjects, and six used 48 laboratory rats housed in 24 cages in the Rodent Animal Holding Facility.

Left: Liftoff of space shuttle Columbia on the STS-58 Spacelab Life Sciences 2 mission. Right: View of the Spacelab module in Columbia’s payload bay.

Space shuttle Columbia’s 15th liftoff took place at 10:53 a.m. EST on Oct. 18, 1993, from Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, carrying the SLS-2 mission into space. Blaha, making his fourth trip into space and second as commander, and Pilot Searfoss on his first launch, monitored Columbia’s systems as they climbed into orbit, assisted by McArthur, also on his first flight, serving as the flight engineer. Seddon, making her third trip into space, accompanied them on the flight deck. Wolf, Lucid, and Fettman experienced launch in the shuttle’s middeck. Upon reaching orbit, the crew opened the payload bay doors, thus deploying the shuttle’s radiators. Shortly after, the crew opened the hatch from the shuttle’s middeck, translated down the transfer tunnel, and entered Spacelab for the first time, activating the module, and getting to work on the experiments, including the first blood draws for the regulatory physiology experiments. The blood samples, stored in the onboard refrigerator for postflight analysis, investigated calcium loss in bone and parameters of fluid and electrolyte regulation.

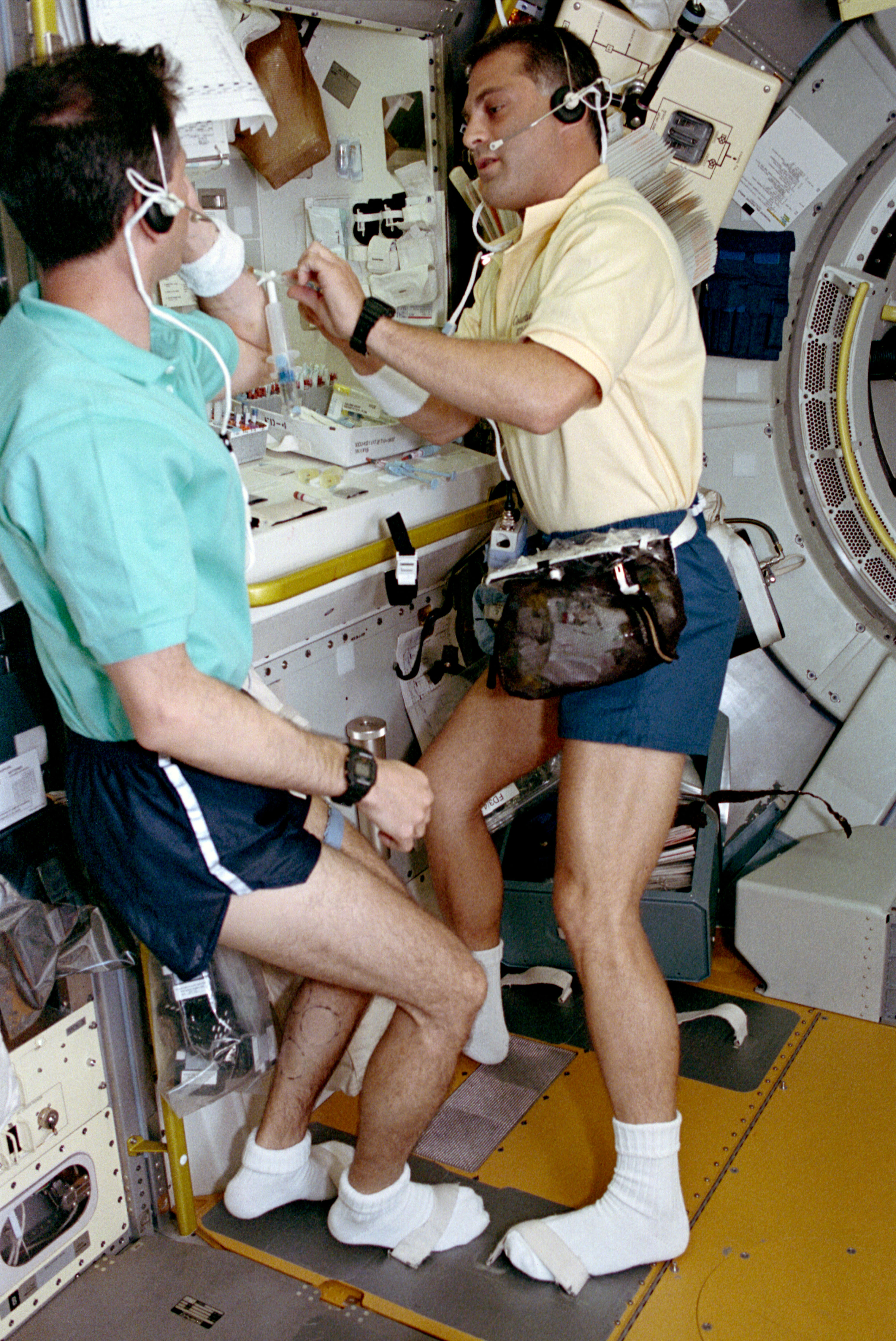

Left: Dr. David A. Wolf draws a blood sample from Dr. Martin J. Fettman as part of a regulatory physiology experiment. Middle: Payload Commander Dr. M. Rhea Seddon processes blood samples. Right: William S. McArthur uses a metabolic gas analyzer to monitor his pulmonary or lung function.

During the 14-day mission, the seven-member SLS-2 crew served as both experiment subjects and operators. The majority of the science activities took place in the Spacelab module mounted in the shuttle’s payload bay, with SLS-2 marking the ninth flight of the ESA-built pressurized module since its first flight on STS-9 in 1983. The experiments had, of course, begun long before launch with extensive baseline data collection. For Lucid and Fettman, data collection for one of the cardiovascular experiments began four hours before launch and continued through ascent and for the first day or so of the mission. Both volunteered to have catheters threaded through an arm vein and into their hearts to directly measure the effect on central venous pressure from the fluid shift caused by the transition to weightlessness.

Two views of the rotating dome experiment, used to measure astronauts’ motion perception, with John E. Blaha, left, and Dr. M. Rhea Seddon, as test subjects.

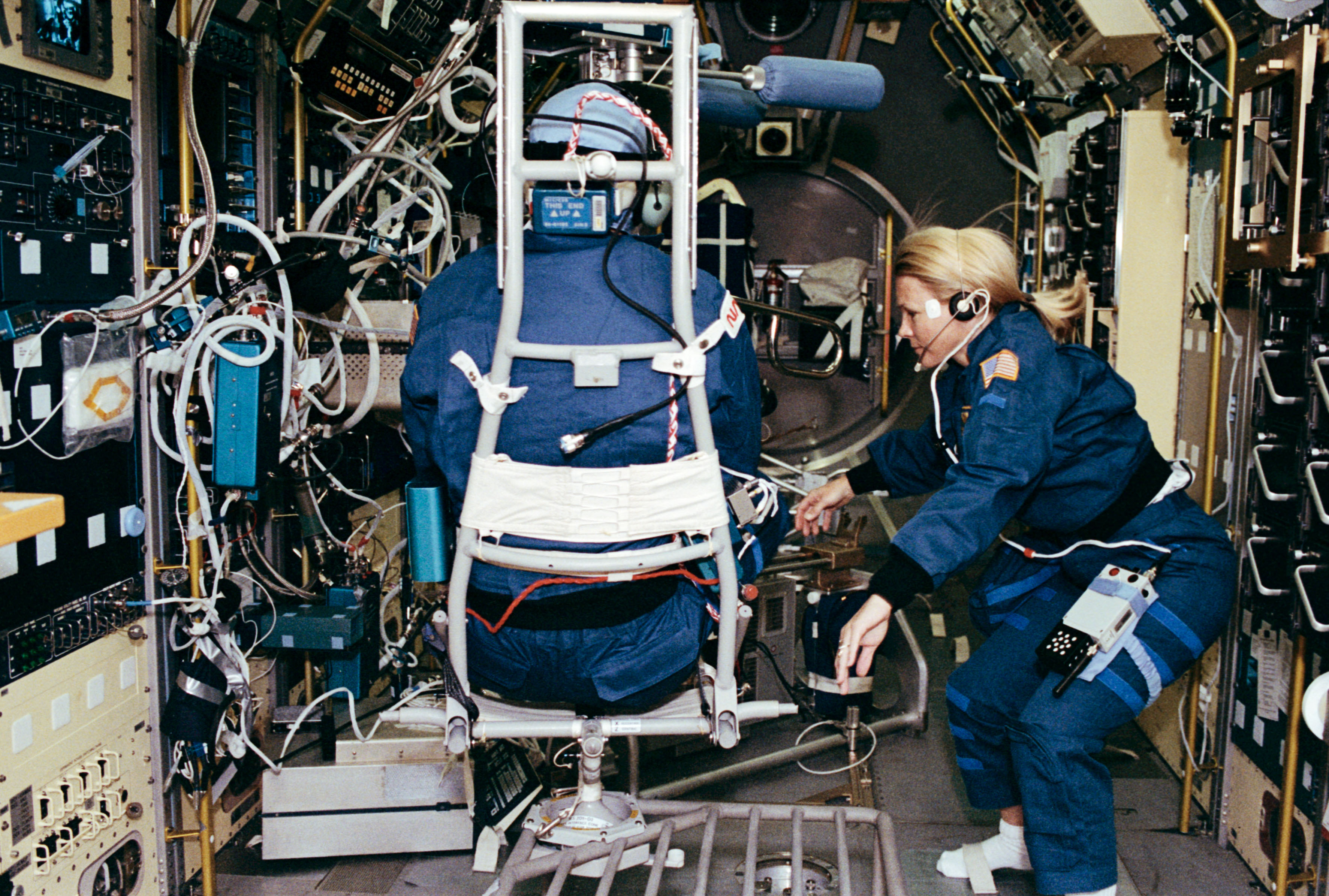

Two views of the rotating chair, with Dr. Martin J. Fettman as the subject and Dr. M. Rhea Seddon as the operator, used to test the astronauts’ vestibular systems.

A group of experiments studied the astronauts’ sensory motor adaptation to spaceflight. In one study, the astronauts placed their heads inside a rotating dome with colored dots painted on its inside surface. Using a joystick, the astronauts indicated in which direction they perceived the rotation of the dots. A rotating chair measured how reflexive eye movements change in weightlessness. Using a bungee harness to simulate falling, astronauts reported on their sensation of and their reflexes to “falling” in microgravity.

A selection of the Earth observation photographs taken by the STS-58 crew. Left: The Memphis, Tennessee, area. Middle left: The Richat Structure in Mauritania. Middle right: Cyprus, Türkiye, and the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Right: Tokyo Bay.

In addition to the complex set of SLS-2 experiments, the STS-58 astronauts’ activities also included other science and operational items. They conducted several experiments as part of the Extended Duration Orbiter Medical Program, including the use of lower body negative pressure as a potential countermeasure to cardiovascular changes, in particular orthostatic intolerance, as shuttle missions flew ever longer missions. The astronauts talked to ordinary people on the ground using the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment, or ham radio. As on all missions, they enjoyed looking at the Earth. When not participating as a test subject for the various experiments or needing to monitor Columbia’s systems, Searfoss in particular took advantage of their unique vantage point, taking more than 4,000 photographs of the Earth below. Blaha and Searfoss tested the Portable In-flight Landing Operations Trainer (PILOT), a laptop computer to help them maintain proficiency in landing the shuttle.

Left: STS-58 astronauts William A. McArthur, top, Martin J. Fettman, David A. Wolf, Richard A. Searfoss, John E. Blaha, M. Rhea Seddon, and Shannon M. Lucid inside the Spacelab module. Middle: McArthur operates the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment, or ham radio. Right: Pilot Searfoss uses the Portable In-flight Landing Operations Simulator, a laptop computer to practice landing the space shuttle.

On their last day in space, the astronauts finished the experiments, Wolf deactivated the Spacelab module, and they strapped themselves into their seats to prepare for the return to Earth. They fired the shuttle’s Orbital Maneuvering System engines to begin the descent from orbit. Blaha piloted Columbia to a smooth landing on Runway 22 at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert on Nov. 1, after completing 225 orbits around the Earth in 14 days and 12 minutes. The astronauts exited Columbia about one hour after landing and transferred to the Crew Transport Vehicle, a converted people-mover NASA purchased from Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C. This allowed them to remain in a supine position to minimize the effects of gravity on the early postflight measurements. While Blaha, Searfoss, and McArthur returned to Houston a few hours after landing, Seddon, Wolf, Lucid, and Fettman continued extensive data collection at the Dryden, now Armstrong, Fight Research Center at Edwards for several days before returning to Houston. Ground crews towed Columbia from the runway to the Mate-Demate Facility to begin preparing it for its ferry flight back to KSC atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and its next mission, STS-62, the United States Microgravity Payload-2 mission.

Left: Space Shuttle Columbia lands at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to end the 14-day STS-58 Spacelab Life Sciences 2 (SLS-2) mission. Right: The seven STS-58 SLS-2 crew members have exited Columbia and transferred to the Crew Transport Vehicle to begin postflight data collection.

Summarizing the scientific return from the flight, Mission Scientist Howard J. Schneider said, “All of our accomplishments exceeded our expectations.” Program Scientist Frank M. Sulzman added, “This has been the best shuttle mission for life sciences to date.” Principal investigators published the results of the experiments from SLS-1 and SLS-2 in a special edition of the Journal of Applied Physiology in July 1996. Enjoy the crew-narrated video about the STS-58 SLS-2 mission.