55 Years Ago: Manned Orbiting Laboratory Cancellation

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), a joint classified project of the U.S. Air Force (USAF) and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), sought to establish a crewed platform in low Earth orbit to obtain high-resolution photographic imagery of America’s 1960s Cold War adversaries. Approved in 1965, the MOL Program envisioned a series of space stations launched from a new pad in California and placed in low polar Earth orbit. Two-man crews, launching and returning to Earth aboard modified Gemini-B capsules, would work aboard the stations for 30 days at a time. Although the Air Force selected 17 pilots and built prototype hardware, the program faced budget pressures and competition from rapidly advancing technologies in uncrewed reconnaissance capabilities, leading to its cancellation on June 10, 1969.

Left: Patch of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) Program. Middle: Illustration of the MOL as it would have appeared in orbit. Image credit: Courtesy National Air and Space Museum. Right: Space Launch Complex-6 under construction in 1966 at Vandenberg Air Force (now Space Force) Base in California. Image credit: Courtesy National Reconnaissance Office.

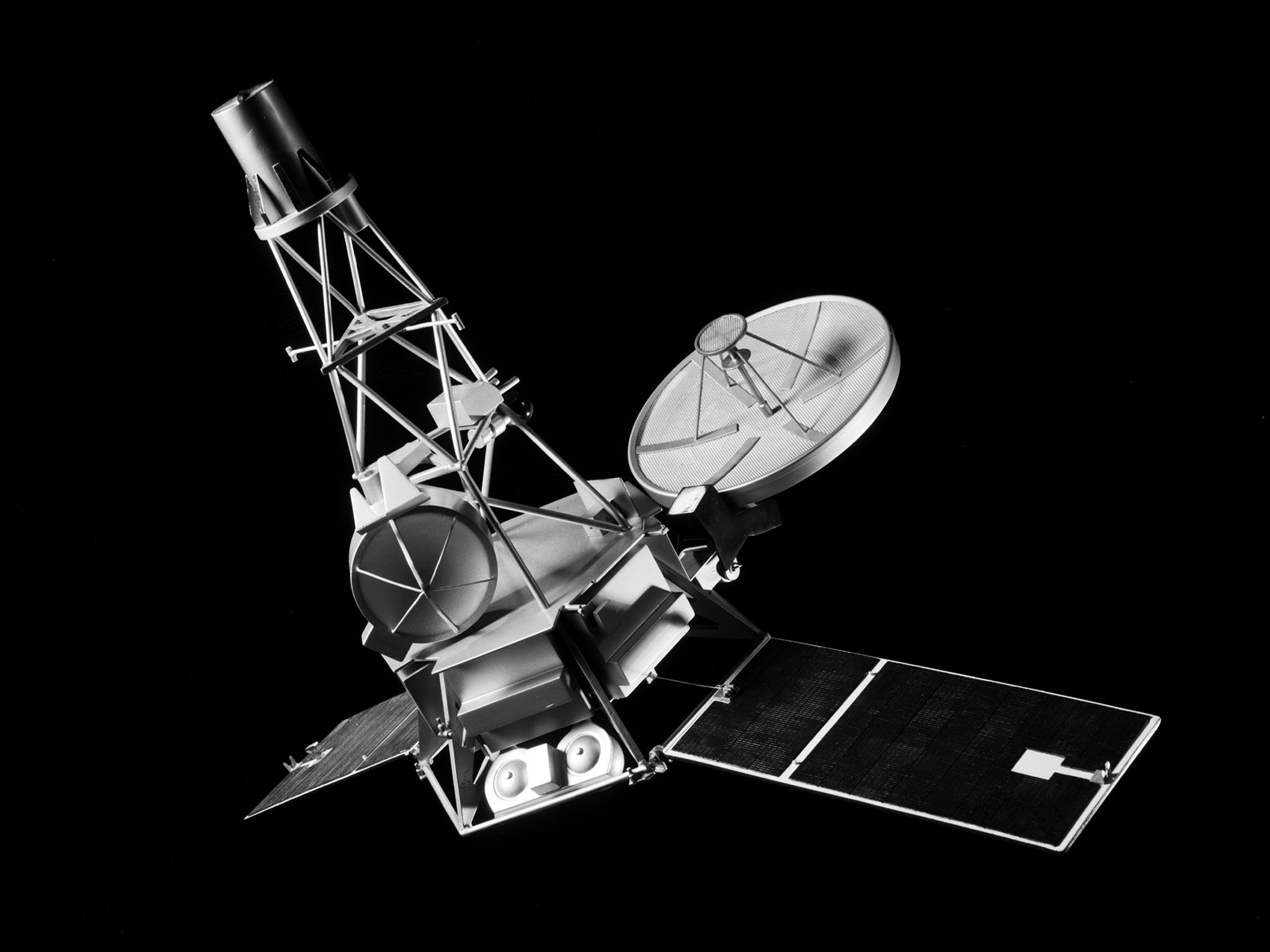

Announced by Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara in December 1963 and formally approved by President Lyndon B. Johnson in August 1965, the MOL Program envisioned a series of 60-foot-long space stations in low polar Earth orbit, occupied by 2-person crews for 30 days at a time, launching and returning to Earth aboard modified Gemini-B capsules. Externally similar to NASA’s Gemini spacecraft, the MOL version’s major modification involved a hatch cut into the heat shield that allowed the astronauts to internally access the laboratory located behind the spacecraft without the need for a spacewalk. While MOL astronauts would carry out a variety of experiments, a telescope with sophisticated imaging systems for military reconnaissance made up the primary payload in the laboratory. The imaging system, codenamed Dorian and carrying the Keyhole KH-10 designation, included a 72-inch diameter primary mirror designed to provide high resolution images of targets of military interest. To reach their polar orbits, MOLs would launch from Vandenberg Air Force (now Space Force) Base (AFB) in California. Construction of Space Launch Complex-6 (SLC-6) there began in March 1966 to accommodate the Titan-IIIM launch vehicle. The sensitive military nature of MOL resulted in its top-secret classification, not declassified by the NRO until October 2015.

The three selection groups of Manned Orbiting Laboratory pilots. Left: Group 1 – Michael J. Adams, Albert H. Crews, John L. Finley, Richard E. Lawyer, Lachlan Macleay, Francis G. Neubeck, James M. Taylor, and Richard H. Truly. Middle: Group 2 – Robert L. Crippen, Robert F. Overmyer, Karol J. Bobko, C. Gordon Fullerton, and Henry W. Hartsfield. Right: Group 3 – Robert T. Herres, Robert H. Lawrence, Donald H. Peterson, and James A. Abrahamson. Image credits: Courtesy U.S. Air Force.

The USAF selected 17 pilots in three groups for the MOL program. The first group, selected on Nov. 12, 1965, consisted of eight pilots – Michael J. Adams, Albert H. Crews, John L. Finley, Richard E. Lawyer, Lachlan Macleay, Francis G. Neubeck, James M. Taylor, and Richard H. Truly. Adams retired from the MOL program in July 1966 to join the X-15 program. While making his seventh flight, he died in November 1967 when his aircraft crashed. Finley left the program in April 1968, returning to the U.S. Navy. The second group, selected on June 17, 1966, consisted of five pilots – Karol J. “Bo” Bobko, Robert L. Crippen, C. Gordon Fullerton, Henry W. Hartsfield, and Robert F. Overmyer. The third and final group of four pilots, chosen on June 30, 1967, comprised James A. Abrahamson, Robert T. Herres, Robert H. Lawrence, and Donald H. Peterson. Lawrence has the distinction as the first African American selected as an astronaut by any national space program. He died in the crash of an F-104 in December 1967.

Group photo of 14 of the 15 Manned Orbiting Laboratory pilots still in the program in early 1968 – John L. Finley, front row left, Richard E. Lawyer, James M. Taylor, Albert H. Crews, Francis G. Neubeck, and Richard H. Truly; Robert T. Herres, back row left, James W. Hartsfield, Robert F. Overmyer, C. Gordon Fullerton, Robert L. Crippen, Donald H. Peterson, Karol J. Bobko, and James A. Abrahamson. Michael J. Adams had left the program and died in an X-15 crash, Robert H. Lawrence had died in a F-104 crash, and Lachlan Macleay does not appear for unknown reasons.

The only space launch in the MOL program occurred on Nov. 3, 1966, when a Titan-IIIC rocket took off from Cape Canaveral Air Force (now Space Force) Station’s Launch Complex 40. The rocket carried a MOL mockup, without the KH-10 imaging payload, and a Gemini-B capsule refurbished after it flew NASA’s uncrewed Gemini 2 suborbital mission in January 1965. This marked the only reflight of an American spacecraft intended for human spaceflight until the advent of the space shuttle. The flight successfully demonstrated the hatch in the heat shield design during the capsule’s reentry after a 33-minute suborbital flight. Sailors aboard the U.S.S. La Salle (LPD-3) recovered the Gemini-B capsule near Ascension Island in the South Atlantic Ocean and returned it to the Air Force for postflight inspection. Visitors can view it on display at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Museum. The MOL mockup entered Earth orbit and released three satellites. It also carried a suite of 10 experiments called Manifold, ranging from cell growth studies to tests of new technologies. Although the experiments could have operated for 75 days, the MOL stopped transmitting after 30 days, and decayed from orbit Jan. 9, 1967.

Left: The only operational launch of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, a Gemini-B capsule and a MOL mockup atop a Titan-IIIC rocket in 1966. Middle: The flown Gemini-B capsule on display at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Museum in Florida. Right: Former MOL and NASA astronaut Robert L. Crippen stands beside the only flown Gemini-B capsule – note the hatch in the heat shield at top.

By 1969, the MOL program ran several years behind schedule and significantly over budget, and other than the one test flight had not flown any actual hardware. Although no flight hardware yet existed, aside from the long lead time mirrors for the imaging system, plans in May 1969 called for four 30-day MOL missions at 6-month intervals starting in January 1972. However, technology for uncrewed military reconnaissance had advanced to the stage that the KH-10 system proposed for MOL had reached obsolescence. Following a review, the new administration of President Richard M. Nixon, faced with competing priorities for the federal budget, announced the cancellation of the MOL program on June 10, 1969.

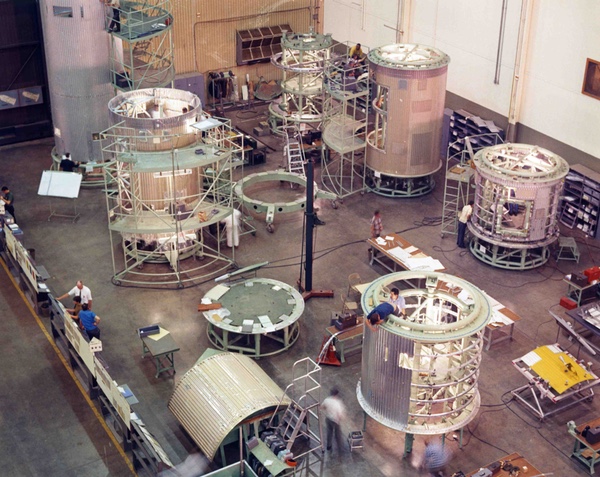

Left: Prototypes of elements of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) under construction. Middle: Medium fidelity mockup of the MOL crew cabin, with suited crew member and the narrow tunnel leading to the Gemini-B capsule. Right: Former MOL and NASA astronaut Robert L. Crippen stands next to the spacesuit developed for the MOL program. Image credits: Courtesy National Reconnaissance Office.

Although the sudden cancellation came as a shock to those working on the program, some of the personnel involved as well as some of the hardware developed for it, made their way into other agencies and projects. For example, the Air Force had developed a flexible spacesuit required by the MOL pilots to navigate through the narrow tunnel between the Gemini-B capsule and the laboratory – that technology transferred to NASA for future spacesuit development. The waste management system designed for use by MOL pilots flew aboard Skylab. The MOL laboratory simulator and the special computer to operate it also transferred to NASA. The technology developed for the acquisition and tracking system and the mission development simulator for the KH-10 imaging system found its way into NASA’s earth remote sensing program.

Official NASA photograph of the Group 7 astronauts – Karol J. Bobko, left, C. Gordon Fullerton, Henry W. Hartsfield, Robert L. Crippen, Donald H. Peterson, Richard H. Truly, and Robert F. Overmyer – transfers from the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program.

After the cancellation of the MOL program, NASA invited the younger (under 35) MOL pilots to join its astronaut corps. Bobko, Crippen, Fullerton, Hartsfield, Overmyer, Peterson, and Truly transferred to NASA on August 14, 1969, as the Group 7 astronaut class. In 1972, Crippen and Bobko participated in the 56-day ground-based Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test, a key activity that contributed to Skylab’s success. Although it took nearly 12 years for the first of the MOL transfers to make it to orbit, all of them went on to fly on the space shuttle in the 1980s, six of them as commanders. In an ironic twist, NASA assigned Crippen to command the first space shuttle polar orbiting mission (STS-62A) that would have launched from the SLC-6 pad at Vandenberg in 1986. But after the January 1986 Challenger accident, the Air Force reduced its reliance on the shuttle as a launch platform and cancelled the mission. Truly served as NASA administrator from 1989 to 1992 and Crippen as the director of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida from 1992 to 1995. NASA hired Crews, not as an astronaut but as a pilot, and he stayed with the agency until 1994. Of the MOL astronauts that did not meet NASA’s age limit requirement, many went on to have stellar careers. Abrahamson joined NASA in 1981 as associate administrator for manned space flight, then went on to lead the Strategic Defense Initiative from 1984 to 1989. Herres served as vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1987 to 1990.

Left: Space shuttle Enterprise during fit checks at the SLC-6 launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force (now Space Force) Base in 1985. Middle: Athena rocket awaits launch on SLC-6 in 1997. Right: Delta-IV Heavy lifts off from SLC-6 in 2011.

Following cancellation of the MOL program, the Air Force mothballed the nearly completed SLC-6 at Vandenberg. In 1972, the Air Force and NASA began looking at SLC-6 as a pad to launch space shuttles with payloads requiring polar orbits, with the decision made in 1975. Workers began converting SLC-6 to launch the space shuttle in 1979. Although space shuttle Enterprise used SLC-6 for fit checks in 1985, the Challenger accident the following year caused the Air Force to cancel plans to use the space shuttle to launch polar orbiting satellites, and they once again mothballed the pad. Following modifications, small Athena rockets used the pad between 1995 and 1999, the first launches from the facility after 30 years of development and modifications. Another conversion begun in 1999 modified SLC-6 to launch Delta-IV and Delta-IV Heavy rockets starting in 2006, with the last flight in 2022. SpaceX leased SLC-6 in April 2023 to begin launches of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets in 2025.

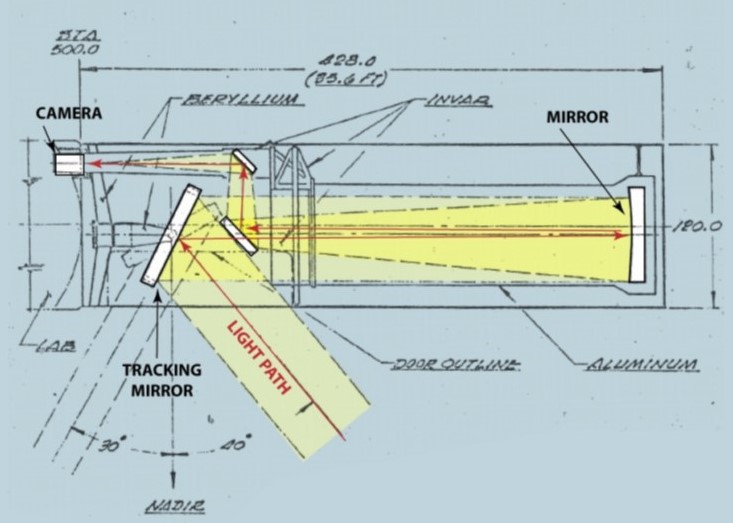

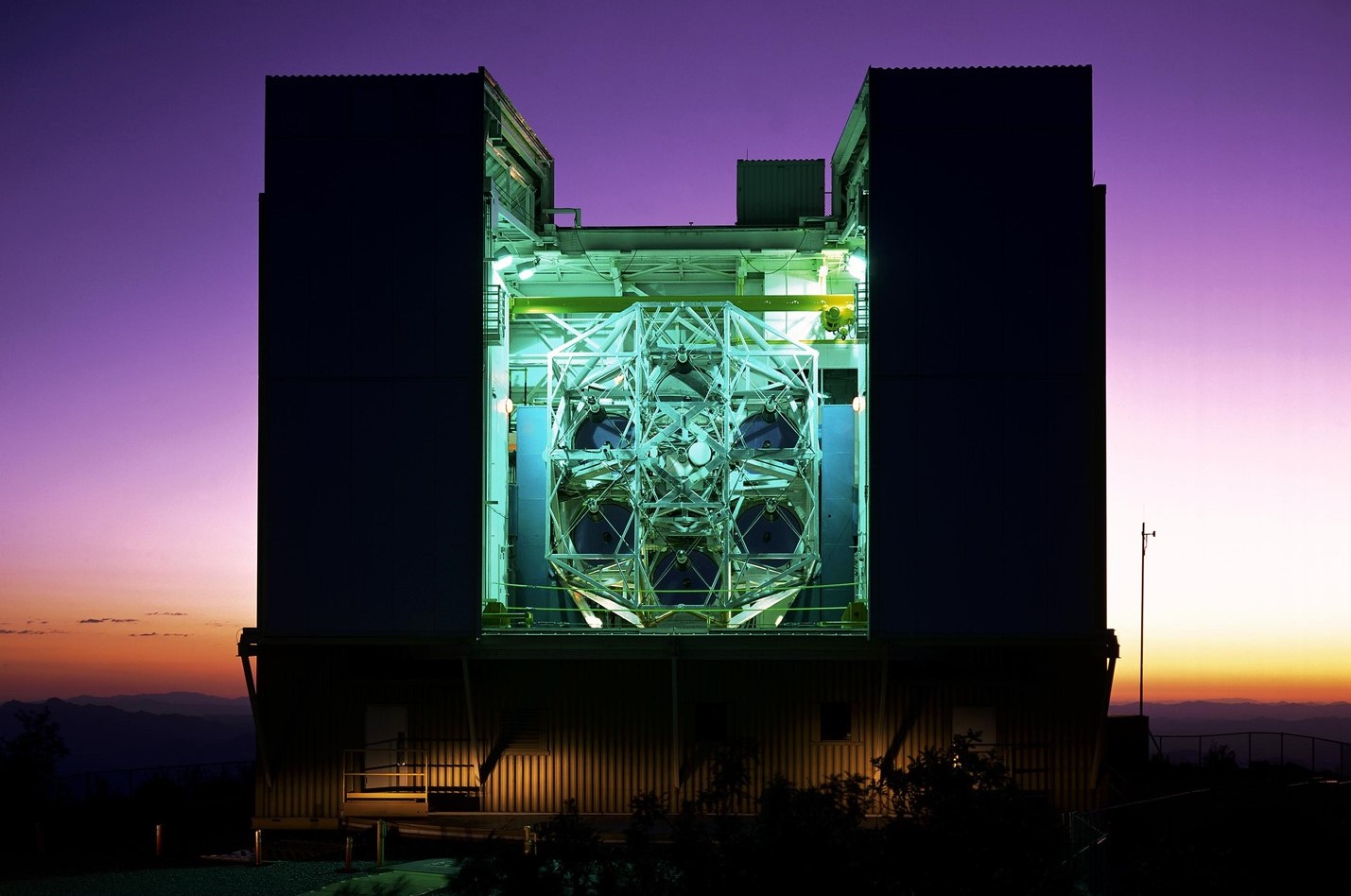

Left: Schematic of the optical system of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), including the 72-inch primary mirror at right. Image credit: courtesy: NRO. Right: The Multiple Mirror Telescope Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona, in its original six-mirror configuration using mirrors from the MOL Program. Image credit: Courtesy Multiple Mirror Telescope.

The NRO transferred six surplus 72-inch mirrors from the cancelled KH-10 program to the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory for the Multiple-Mirror Telescope (MMT) it built in association with the University of Arizona, located on Mount Hopkins, Arizona. By combining the light of the six mirrors, they achieved an effective light collecting area of a single 177-inch telescope mirror. The MMT operated in this six-mirror configuration for nearly 20 years before a single 215-inch mirror replaced them.

Read Abrahamson’s, Bobko’s, Crew’s, Crippen’s, Fullerton’s, Hartsfield’s, Peterson’s, and Truly’s recollections of the MOL program in their oral history interviews with the JSC History Office. In 2019, the NRO held a panel discussion with MOL pilots Abrahamson, Bobko, Macleay, Crews, and Crippen, by then free to talk about their experiences during the now declassified program.