NASA Collaborating on European-led Gravitational Wave Observatory in Space

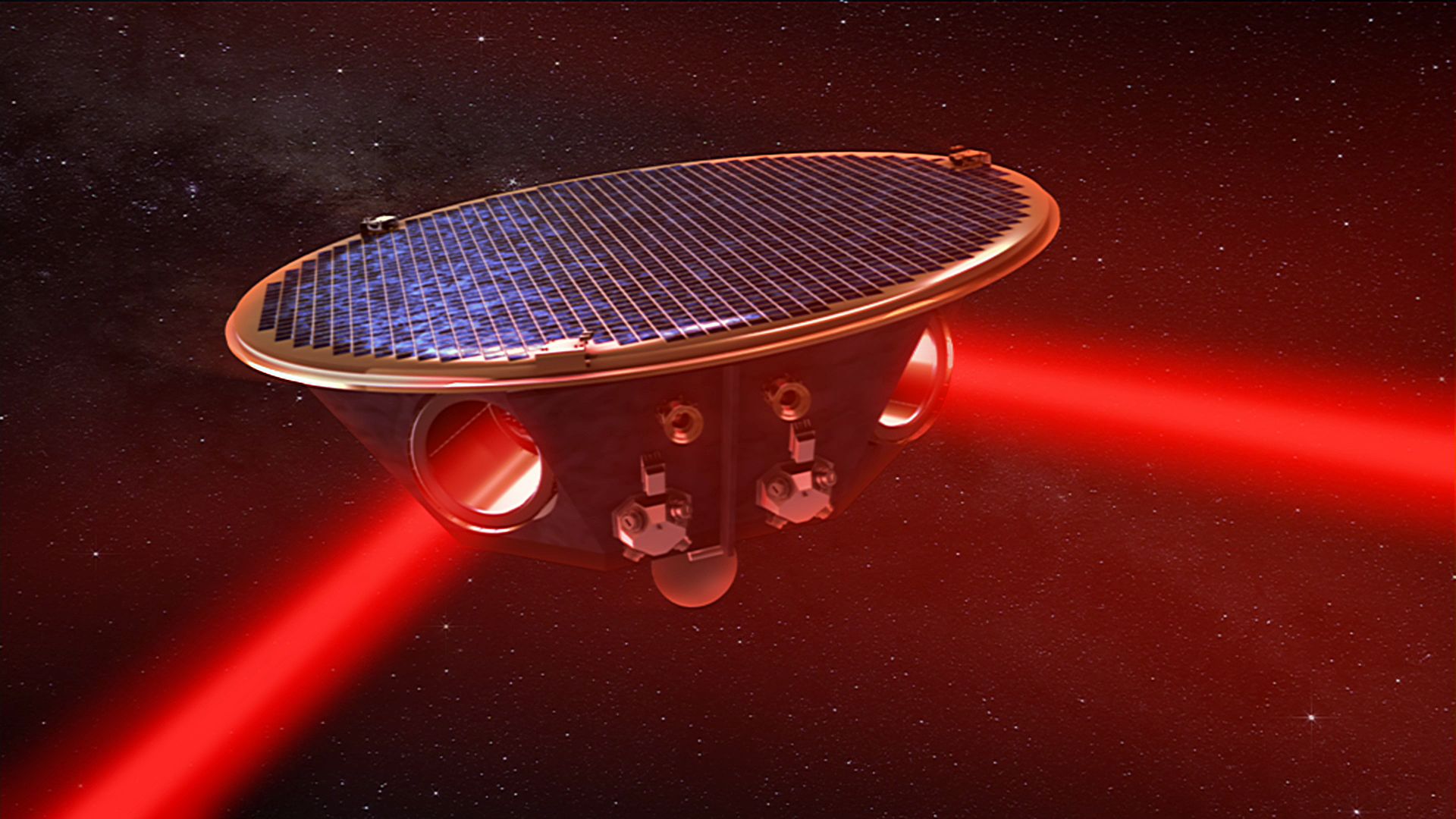

The first space-based observatory designed to detect gravitational waves has passed a major review and will proceed to the construction of flight hardware. On Jan. 25, ESA (European Space Agency), announced the formal adoption of LISA, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, to its mission lineup, with launch slated for the mid-2030s. ESA leads the mission, with NASA serving as a collaborative partner.

“In 2015, the ground-based LIGO observatory cracked open the window into gravitational waves, disturbances that sweep across space-time, the fabric of our universe,” said Mark Clampin, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “LISA will give us a panoramic view, allowing us to observe a broad range of sources both within our galaxy and far, far beyond it. We’re proud to be part of this international effort to open new avenues to explore the secrets of the universe.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=i2u-7LMhwvE%3Ffeature%3Doembed%26enablejsapi%3D1%26html5%3D1%26origin%3Dhttps%3A

The LISA mission will enable observations of gravitational waves produced by merging supermassive black holes, seen here in a computer simulation. Most big galaxies contain central black holes weighing millions of times the mass of our Sun. When these galaxies collide, eventually their black holes do too. Download high-resolution video from NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Scott Noble; simulation data, d’Ascoli et al. 2018

NASA will provide several key components of LISA’s instrument suite along with science and engineering support. NASA contributions include lasers, telescopes, and devices to reduce disturbances from electromagnetic charges. LISA will use this equipment as it measures precise distance changes, caused by gravitational waves, over millions of miles in space. ESA will provide the spacecraft and oversee the international team during the development and operation of the mission.

Gravitational waves were predicted by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity more than a century ago. They are produced by accelerating masses, such as a pair of orbiting black holes. Because these waves remove orbital energy, the distance between the objects gradually shrinks over millions of years, and they ultimately merge.

These ripples in the fabric of space went undetected until 2015, when LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, measured gravitational waves from the merger of two black holes. This discovery furthered a new field of science called “multimessenger astronomy” in which gravitational waves could be used in conjunction with the other cosmic “messengers” – light and particles – to observe the universe in new ways.

Along with other ground-based facilities, LIGO has since observed dozens more black hole mergers, as well as mergers of neutron stars and neutron star-black hole systems. So far, the black holes detected through gravitational waves have been relatively small, with masses of tens to perhaps a hundred times that of our Sun. But scientists think that mergers of much more massive black holes were common when the universe was young, and only a space-based observatory could be sensitive to gravitational waves from them.

“LISA is designed to sense low-frequency gravitational waves that instruments on Earth cannot detect,” said Ira Thorpe, the NASA study scientist for the mission at the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “These sources encompass tens of thousands of small binary systems in our own galaxy, as well as massive black holes merging as galaxies collided in the early universe.”

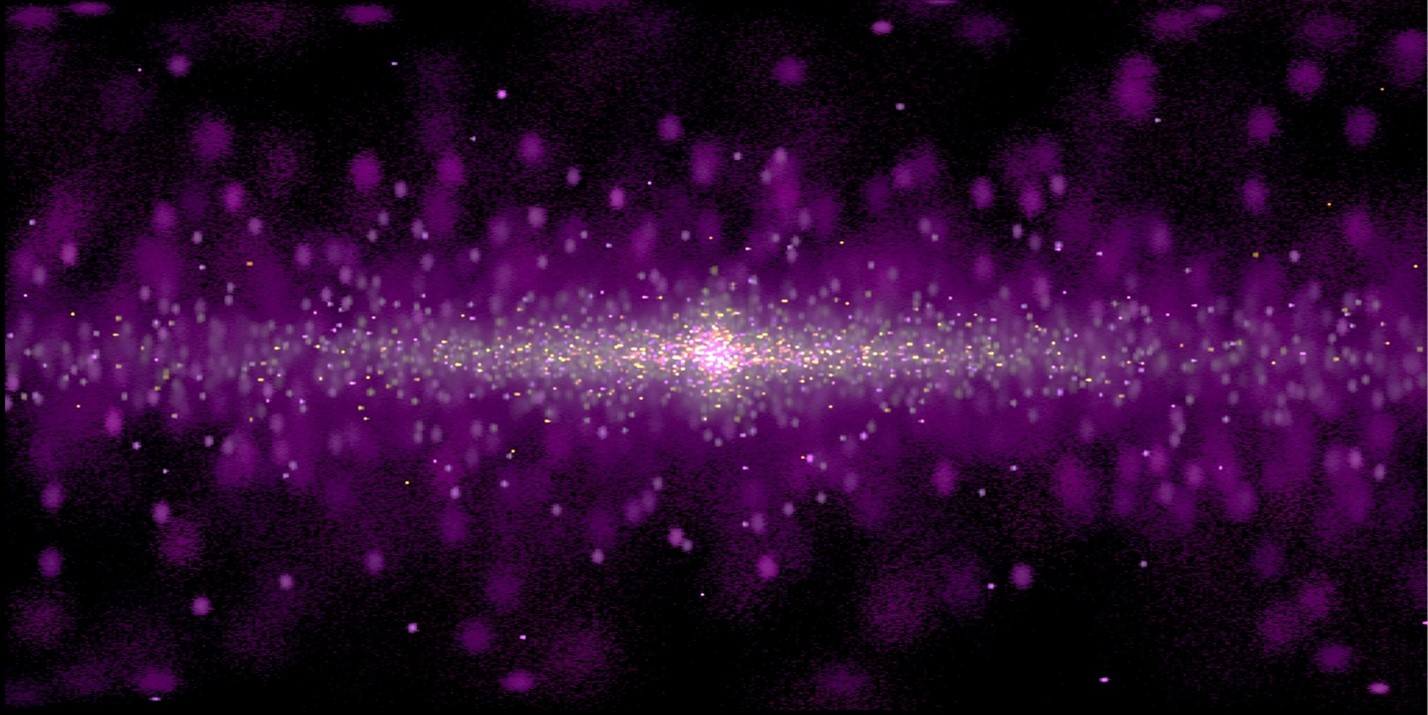

Gravitational waves from a simulated population of compact binary systems in our galaxy were used to construct this synthetic map of the entire sky. Such systems contain white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes in tight orbits. Maps like this using real data will be possible once the LISA mission becomes active in the next decade. The center of our Milky Way galaxy lies at the center of this all-sky view, with the galactic plane extending across the middle. Brighter spots indicate sources with stronger gravitational signals and lighter colors indicate those with higher frequencies. Larger colored patches show sources whose positions are less well known.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

LISA will consist of three spacecraft flying in a vast triangular formation that follows Earth in its orbit around the Sun. Each arm of the triangle stretches 1.6 million miles (2.5 million kilometers). The spacecraft will track internal test masses affected only by gravity. At the same time, they’ll continuously fire lasers to measure their separations to within a span smaller than the size of a helium atom. Gravitational waves from sources throughout the universe will produce oscillations in the lengths of the triangle’s arms, and LISA will capture these changes.

The underlying measurement technology was successfully demonstrated in space with ESA’s LISA Pathfinder mission, which operated between 2015 and 2017 and also included NASA participation. The spacecraft demonstrated the exquisite control and precise laser measurements needed for LISA.

By Francis Reddy

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.