15 Years Ago: STS-125, the Final Hubble Servicing Mission

“Trying to do stellar observations from Earth is like trying to do birdwatching from the bottom of a lake.” James B. Odom, Hubble Program Manager 1983-1990.

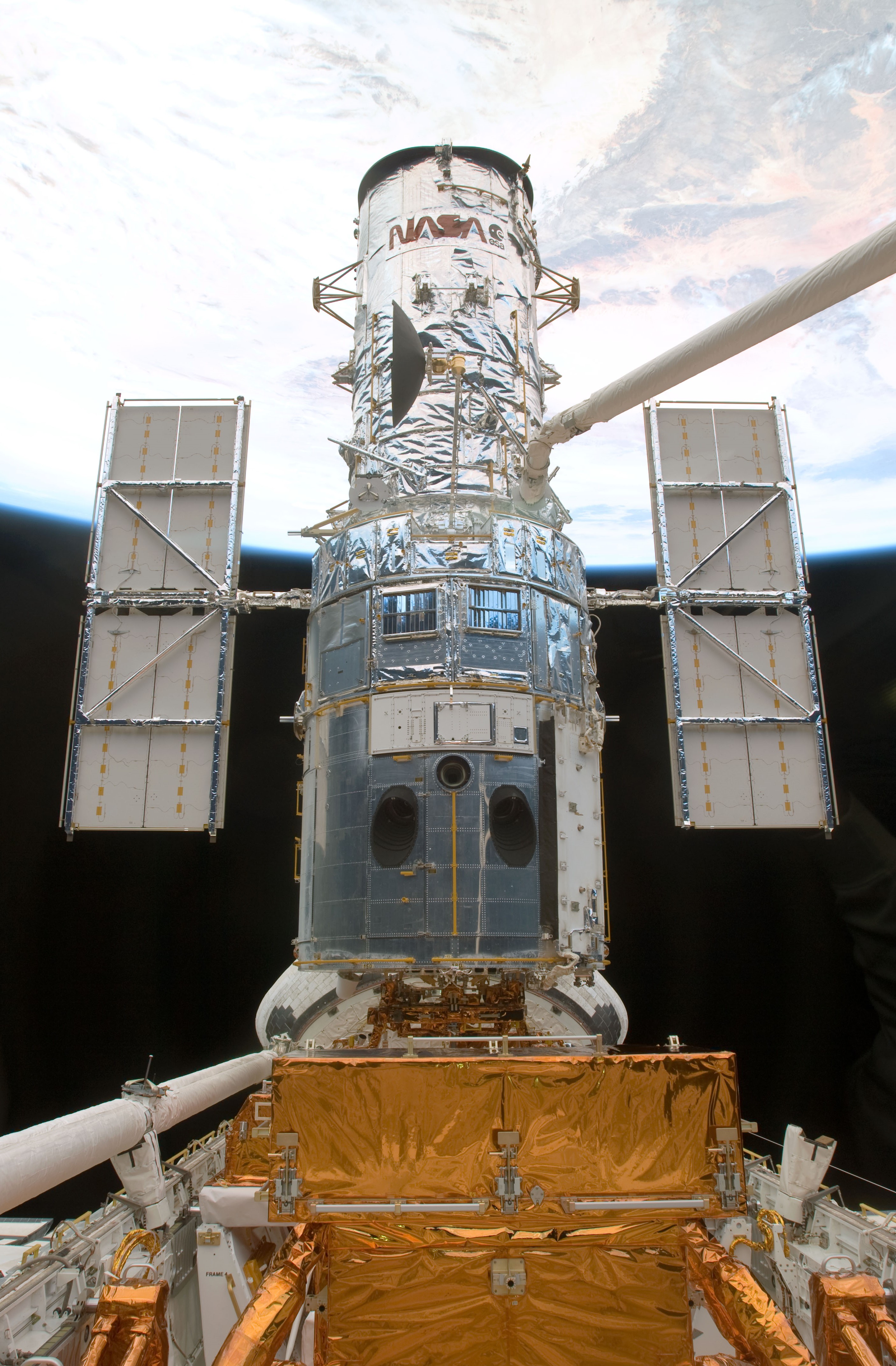

The fifth and final servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope, placed in orbit in 1990, took place during the STS-125 mission in May 2009. During the 13-day flight, the seven-member crew rendezvoused with and captured Hubble, conducted five complex spacewalks to service and upgrade the telescope, and redeployed it, giving it greater capabilities than ever before to help scientists unlock the secrets of the universe. The telescope continues to operate, far exceeding the five-year life extension expected from the servicing mission. Joined in space by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2021, the two instruments together can image the skies across a broad range of the electromagnetic spectrum to provide scientists with the tools to gain unprecedented insights into the universe and its formation.

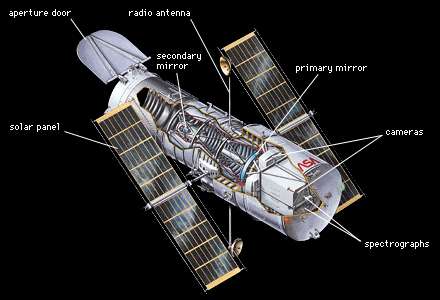

Left: Schematic showing the Hubble Space Telescope’s major components. Middle: Workers inspect the Hubble Space Telescope’s 94-inch diameter primary mirror prior to assembly. Right: Astronauts release the Hubble Space Telescope in April 1990 during the STS-31 mission.

The discovery after the Hubble Space Telescope’s launch in 1990 that its primary mirror suffered from a flaw called spherical aberration disappointed scientists who could not obtain the sharp images they had expected. But thanks to the Hubble’s built-in feature of on-orbit servicing, NASA devised a plan to correct the telescope’s optics during the first planned repair mission in 1993. Three additional servicing missions in 1997, 1999, and 2002, upgraded the telescope’s capabilities. As the shuttle’s retirement in 2011 approached, NASA decided the benefits of extending Hubble’s life outweighed the risks posed by one final servicing mission. To execute the final Hubble Servicing Mission, NASA assigned Commander Scott D. Altman, Pilot Gregory C. Johnson, and Mission Specialists Michael T. Good, K. Megan McArthur, John M. Grunsfeld, Michael J. Massimino, and Andrew J. Feustel. Altman, Grunsfeld, and Massimino had traveled together to Hubble before on the previous servicing mission, STS-109, in 2002, and Grunsfeld had serviced Hubble on an earlier mission, STS-103, three years before that. For Johnson, Good, McArthur, and Feustel, STS-125 marked their first trip into space.

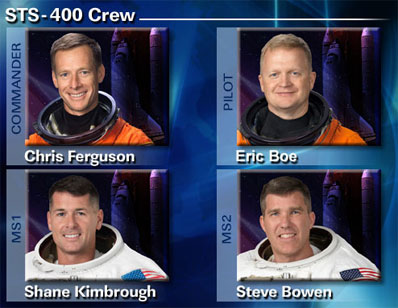

Left: The STS-125 crew of Michael J. Massimino, left, Michael T. Good, Gregory C. Johnson, Scott D. Altman, K. Megan McArthur, John M. Grunsfeld, and Andrew J. Feustel. Middle: The STS-125 crew patch. Right: The STS-400 crew of Christopher J. Ferguson, upper left, Eric A. Boe, R. Shane Kimbrough, and Stephen G. Bowen.

In January 2004, in the wake of the Columbia accident NASA Administrator Sean C. O’Keefe canceled the fifth and final Hubble Servicing Mission. O’Keefe believed the mission too risky, citing the lack of a safe haven and rescue capability in case the shuttle suffered damage similar to Columbia’s. In October 2006, his successor Administrator Michael D. Griffin reversed the decision, reinstating the mission targeting launch in May 2008. Delays in development caused the target launch date to slip to October. Griffin approved the flight with the constraint that another shuttle, in this case Endeavour, would stand ready to launch in the very unlikely event Atlantis’ crew needed rescuing. Griffin believed that the risk reduction that the rescue mission presented justified the additional science gained from extending Hubble’s on orbit lifetime. NASA designated the standby mission STS-400 and initially assigned NASA astronauts Dominic L. Gorie, Gregory H. Johnson, Robert L. Behnken, and Michael J. Foreman, the flight deck crew from the recently flown STS-123, to train for the launch-on-need rescue. After STS-126, NASA replaced them with that mission’s flight deck crew of Christopher J. Ferguson, Eric A. Boe, R. Shane Kimbrough, and Stephen G. Bowen.

Left: In the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers lift Atlantis to mate it to its External Tank and Solid Rocket Boosters. Middle: Shuttles on two pads for the first launch attempt, Atlantis on Pad 39A, left, and Endeavour on Pad 39B. Right: Atlantis rolls back into the VAB.

Although Griffin’s approval cleared the biggest hurdle to flying the final Hubble servicing mission, actually getting it off the ground faced additional challenges. At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, Atlantis rolled out to Launch Pad 39A on Sept. 4, 2008, and Endeavour rolled out to Launch Pad 39B on Sept. 18, marking the first time since 2001 that shuttles occupied both pads. The Hubble servicing payload arrived at Pad 39A on Sept. 22, and workers installed it into Atlantis’ payload bay three days later. The seven astronauts arrived at KSC on Sept. 21 to participate in the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test, a dress rehearsal for the launch planned for Oct. 14. Fate intervened when on Sept. 27, the Science Instrument Command and Data Handling (SIC&DH) Unit aboard Hubble failed. Two days later, NASA decided to delay the servicing mission to February 2009 to include replacement of the failed unit as part of the servicing. This resulted in Atlantis rolling back to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on Oct. 20. Endeavour rolled around from Pad B to Pad A three days later and launched on the STS-126 mission on Nov. 14.

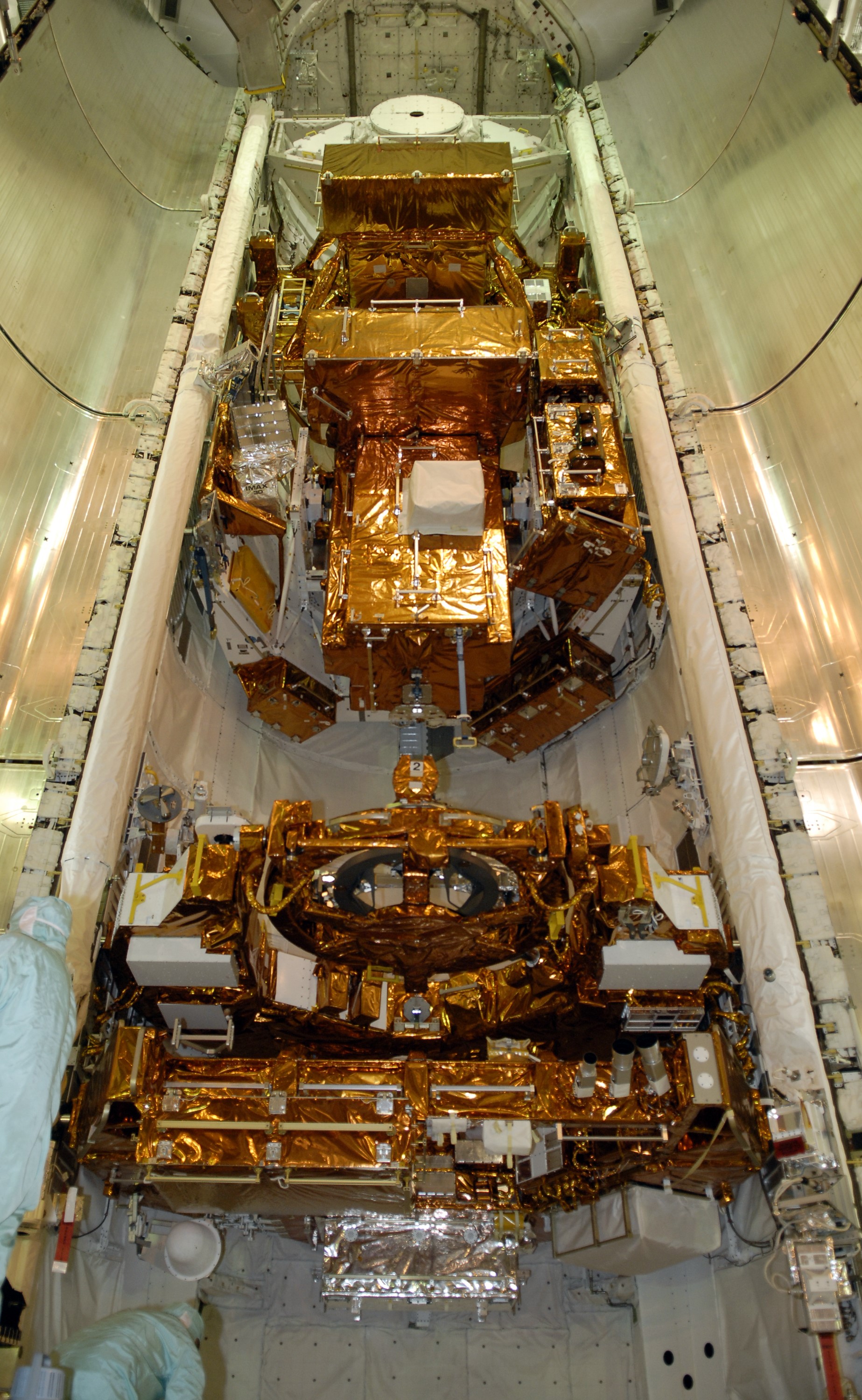

Left: The payload canister, left, arrives at Launch Pad 39A, where Atlantis awaits for the second launch attempt. Middle left: The Hubble Servicing Mission payloads installed in Atlantis’ payload bay. Middle right: Once again, shuttles on two pads, Atlantis on 39A, left, and Endeavour on 39B. Right: The STS-125 crew arrives at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for launch.

Although ground controllers at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, put Hubble back in service by Oct. 30, NASA announced that the hardware to replace the failed SIC&DH unit could not meet a February launch, delaying the servicing mission to May. This required the destacking of Atlantis from its External Tank (ET) and Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) – they would be used to fly Discovery on STS-119 in March – and returning it to the Orbiter Processing Facility for maintenance. On March 23, Atlantis returned to the VAB for stacking with a new ET and SRBs, and rolled out to Pad 39A eight days later. On April 20, Endeavour took up its position on Pad 39B, and once again shuttles occupied both pads. The Flight Readiness Review on April 30 cleared Atlantis to begin its Hubble Servicing Mission on May 11. The seven-member crew arrived on May 8 to begin final preparations for the flight.

Left: With space shuttle Endeavour in the foreground, space shuttle Atlantis takes off to begin the STS-125 fifth and final Hubble Servicing Mission. Middle: STS-125 Commander Scott D. Altman maneuvers Atlantis close to Hubble. Right: Hubble during the rendezvous maneuvers.

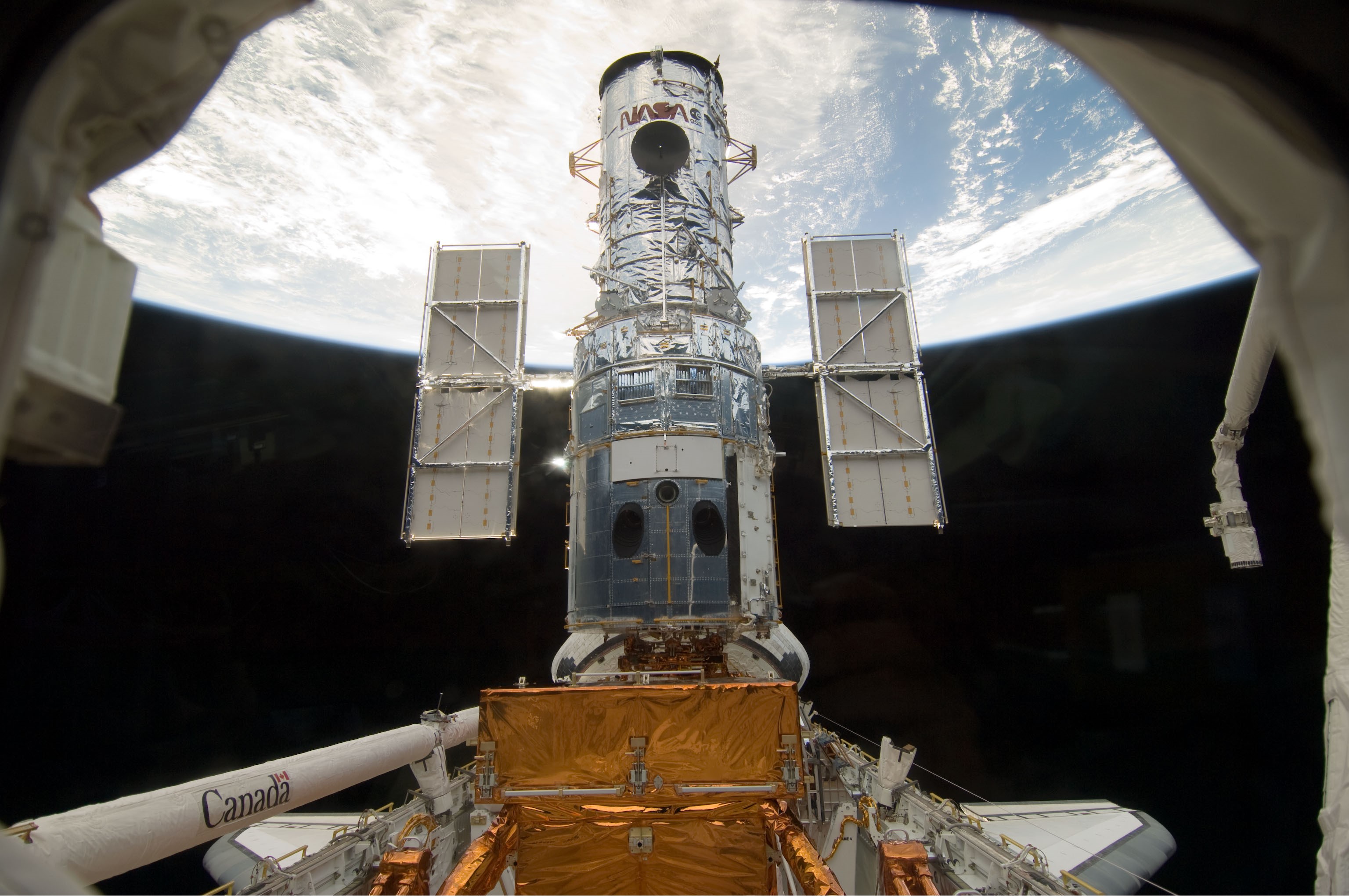

Left: STS-125 astronaut K. Megan McArthur at the controls of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), preparing to grapple Hubble. Middle: McArthur has grappled Hubble with the RMS. Right: Hubble secured in Atlantis’ payload bay.

Following a smooth countdown, space shuttle Atlantis and its seven-member crew lifted off on time from Launch Pad 39A on May 11, 2009, at 2:01 p.m. EDT. Following a smooth ride to orbit, the astronauts began orbital operations by opening the payload bay doors, deploying the Ku-band antenna, and performed a survey of the payload bay using cameras on the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm. They also removed their bulky Launch and Entry Suits (LESs). The astronauts spent much of their second day in space conducting a thorough inspection of the orbiter thermal protection system, using the RMS and the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS), to ensure it didn’t suffer any damage during launch. They prepared the Flight Support System (FSS), used to berth Hubble following its capture, and began checking out the tools they would use during the upcoming spacewalks. On Flight Day 3, Altman and Johnson performed rendezvous maneuvers to bring Atlantis to within 35 feet of Hubble. McArthur grappled the telescope with the RMS and berthed it on the FSS.

First spacewalk. Left: Andrew J. Feustel carries the Wide Field and Planetary Camera-2 (WFPC-2) that he and John M. Grunsfeld removed from Hubble. Middle: Grunsfeld floats next to Hubble, with a large opening where he and Feustel removed WFPC-2 and later installed the Wide Field Camera-3 (WFC-3). Right: Grunsfeld, bottom, and Feustel remove the WFC-3 from its stowage location.

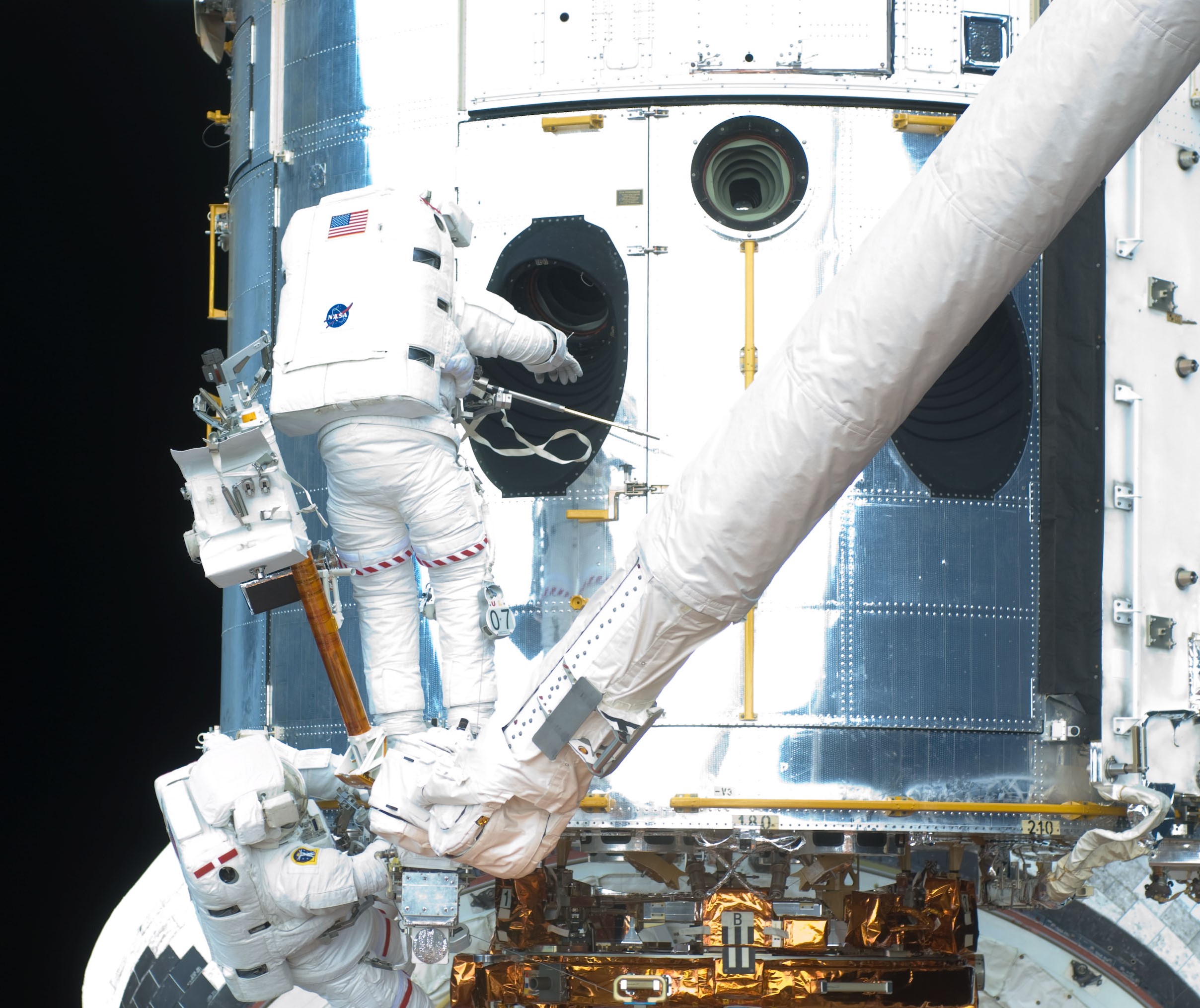

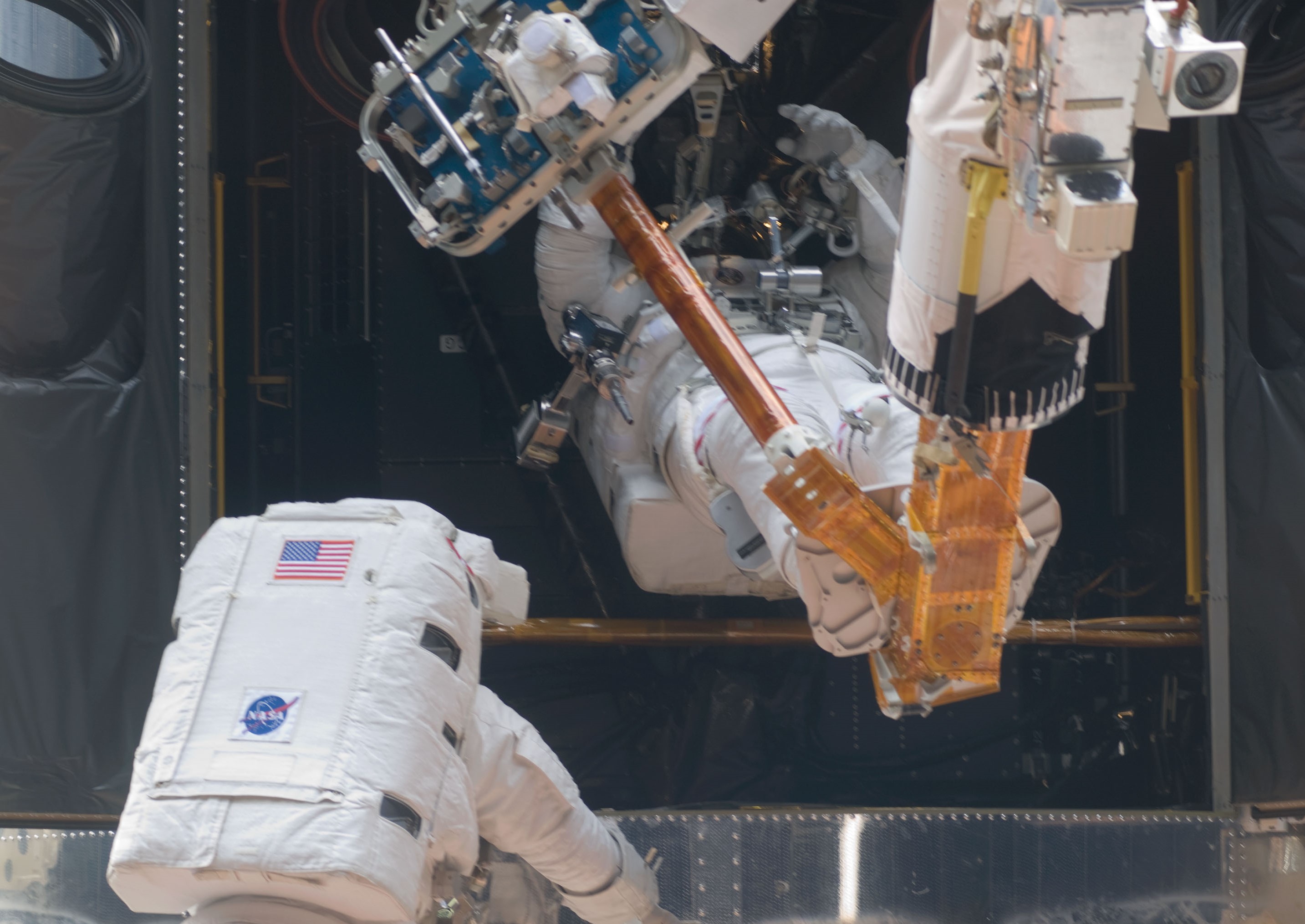

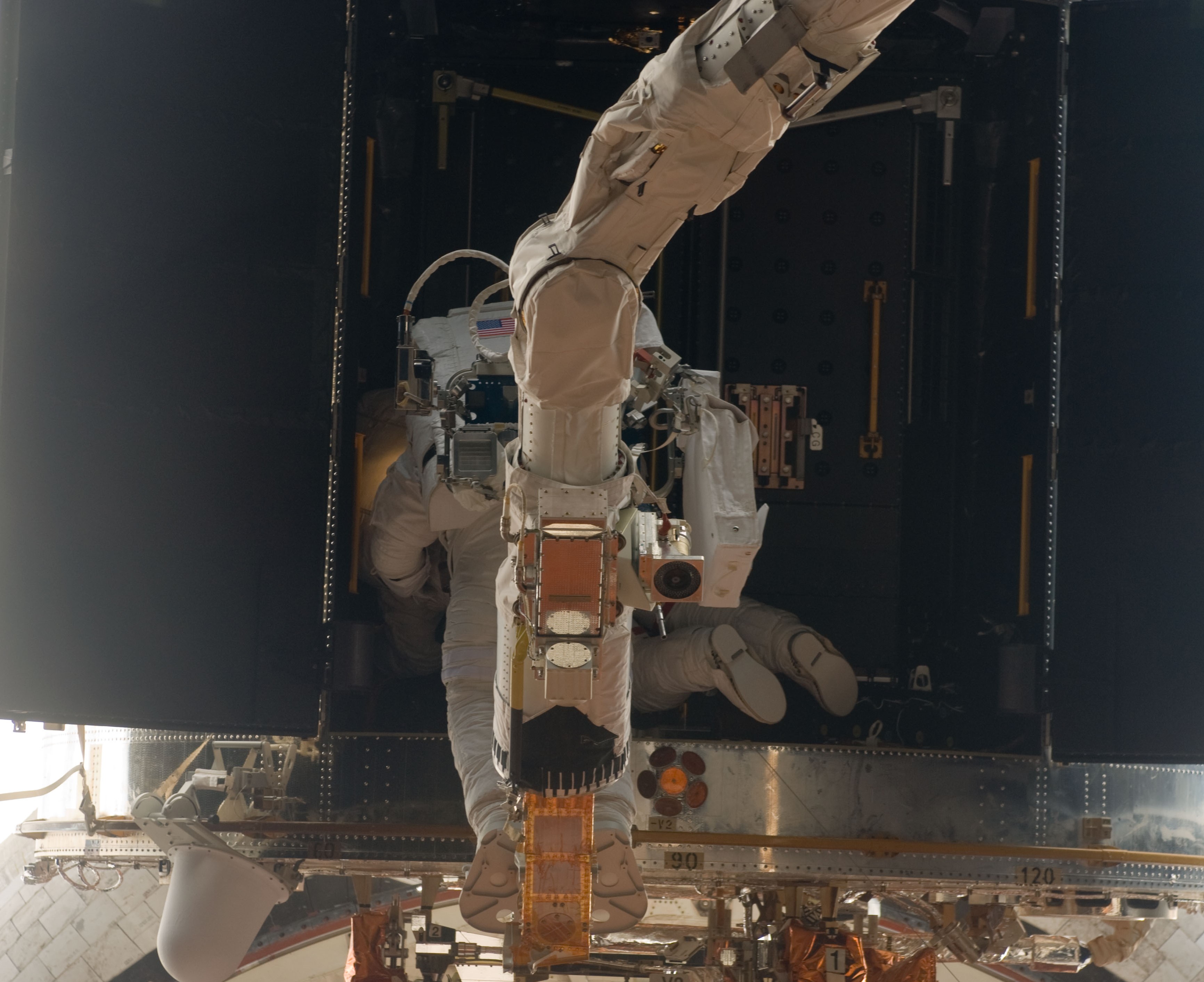

Grunsfeld and Feustel conducted the first spacewalk of the mission on May 10, the flight’s fourth day. McArthur operated the RMS, as she did on all five spacewalks, using it to maneuver one of the spacewalkers perched on the Manipulator Foot Restraint at the end of the arm. After gathering their tools, Grunsfeld and Feustel completed the first major task by removing the Wide Field and Planetary Camera-2, installed during STS-61, the first servicing mission in 1993. After stowing the old camera in the payload bay, they replaced it with the Wide Field Camera-3, allowing Hubble to take large-scale, clear, and detailed images over a wider range of colors than the old instrument. Grunsfeld and Feustel then replaced the SIC&DH unit, the item that failed in September 2008, delaying the servicing mission by seven months. The final task of the first spacewalk involved installing the Soft-Capture Mechanism that included a Low Impact Docking System to allow future spacecraft to dock with to service the telescope or to deorbit it at the end of its useful life. Grunsfeld and Feustel spent seven hours and 20 minutes outside.

Second spacewalk. Left: Michael J. Massimino, bottom, and Michael T. Good prepare to open the panel to begin replacing the gyroscope Rate Sensor Units (RSUs). Middle: Massimino assists Good in replacing the telescope’s three RSUs. Right: Good replacing one of Hubble’s batteries.

The team of Massimino and Good performed the second spacewalk, on Flight Day 5. Their primary task involved removing and replacing Hubble’s three gyroscope Rate Sensing Units (RSUs). Each RSU contained two gyroscopes to allow the telescope to properly orient itself. After initial problems installing one of the units, Massimino and Good installed a spare unit, accomplishing the major task of the spacewalk. They next replaced one of the telescope’s batteries before ending the spacewalk after seven hours and 56 minutes.

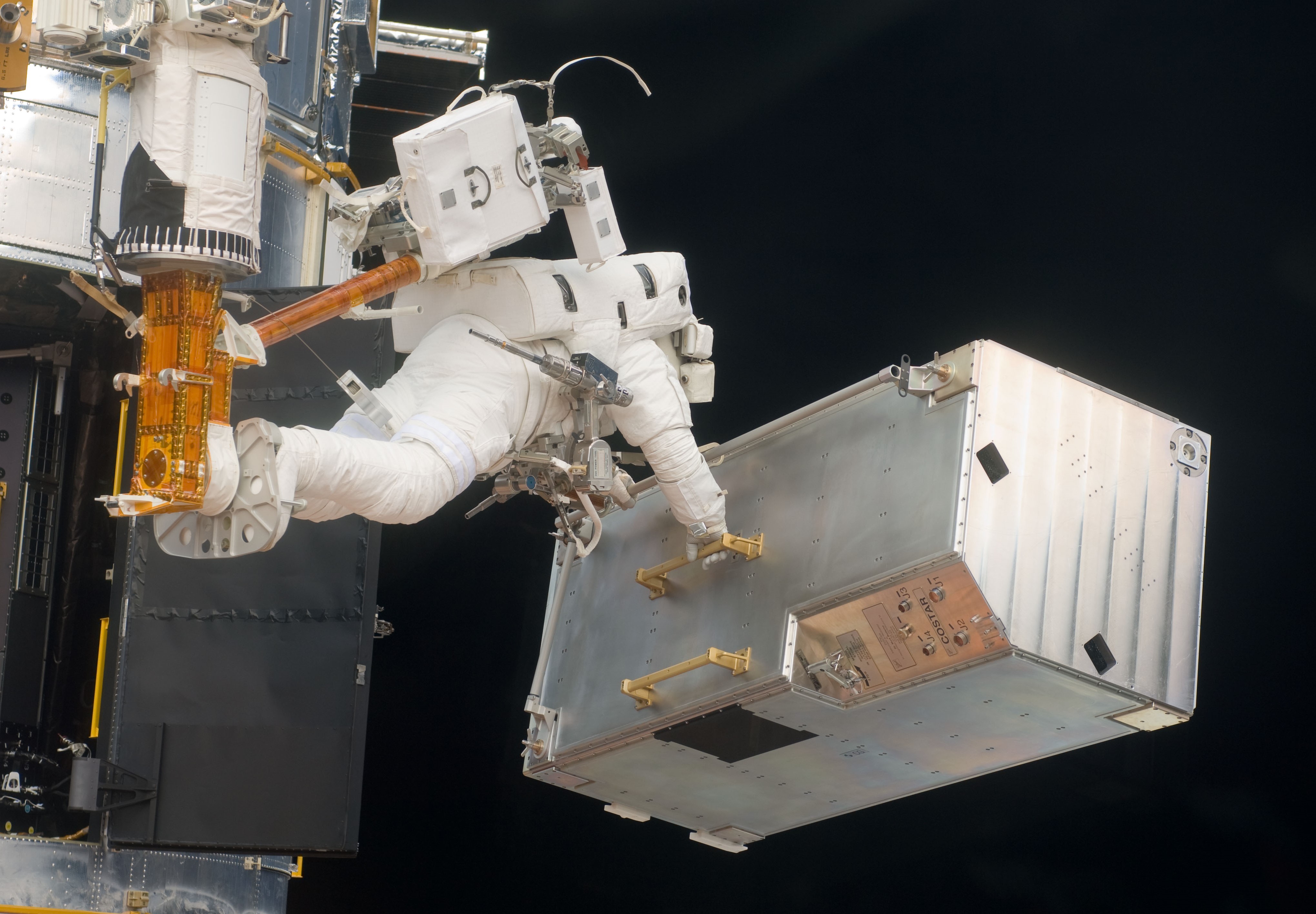

Third spacewalk. Left: Andrew J. Feustel, left, and John M. Grunsfeld remove the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR) instrument. Middle: Feustel carries COSTAR to its stowage location. Right: Feustel, left, and Grunsfeld repair the Advanced Camera for Surveys.

Grunsfeld and Feustel ventured outside again for the mission’s third spacewalk on May 16. Their first task involved removing the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR), installed during the first servicing mission to correct the mirror’s spherical aberration. Grunsfeld and Feustel easily removed COSTAR, stowing it in the payload bay, and replaced it with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph instrument. Running about one hour ahead of the timeline, they moved on to the repair of the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), an instrument that failed in 2007 but not designed for in-orbit repair. Using tools specially designed for the tasks, Grunsfeld and Feustel removed an access panel, replaced the camera’s four circuit boards, and installed a new power supply. They ended their second spacewalk after six hours and 36 minutes.

Fourth spacewalk. Left: Michael T. Good, left, and Michael J. Massimino repair Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS). Middle: Good, left, and Massimino continue repairs of STIS. Right: Massimino, outside, says Hi to K. Megan McArthur.

For the mission’s fourth spacewalk, Massimino and Good ventured out again on May 17. They spent much of the excursion working on the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), an instrument that failed in 2004 due to a power failure. Like the ACS, designers had not intended STIS for in-orbit repair, posing a challenge to the astronauts as the fix required the removal of more than 100 screws. In addition to that time-consuming challenge, Massimino could not remove one of the handrails, causing him to use brute force to remove it. They completed the repair of the STIS although the tasks took much longer than planned, resulting in a spacewalk lasting eight hours and two minutes.

Fifth spacewalk. Left: Andrew J. Feustel, left, and John M. Grunsfeld replace a Fine Guidance Sensor. Middle: Grunsfeld at the end of the Remote Manipulator System. Right: Grunsfeld, left, and Feustel prepare to enter the airlock to conclude the final Hubble servicing spacewalk.

On Flight Day 8, Grunsfeld and Feustel exited the airlock for their third and the mission’s fifth and final spacewalk. They replaced a second battery and removed and replaced a Fine Guidance Sensor. Working about one hour ahead of the timeline, they had time to remove three degraded thermal blankets, replacing them with three new ones, before ending the final Hubble servicing spacewalk after seven hours and two minutes. That brought the total spacewalking time for the mission to 36 hours 56 minutes.

Left: Astronaut K. Megan McArthur grapples the Hubble Space Telescope. Middle left: McArthur lifts the telescope off its cradle prior to release. Middle right: Hubble begins its departure from Atlantis. Right: Hubble at a greater distance.

On May 19, with five consecutive days of complex and arduous spacewalks behind them, the astronauts turned their focus on releasing the newly refurbished space telescope. Using the RMS, McArthur grappled Hubble and lifted it off its FSS and out of the payload bay. As Atlantis flew over Africa, McArthur released the telescope and Altman called down to Houston, “Hubble has been released, it’s safely back on its journey of exploration.” Firing the orbiter’s thrusters, Johnson nudged Atlantis away from Hubble as it sailed over the crew compartment. After a separation burn, the astronauts watched as the telescope drifted away. They turned their attention to completing the late inspection of the shuttle’s heat shield, finding it undamaged.

Left: Inflight photo of the STS-125 crew. Middle: The STS-125 crew provides testimony via television to a Congressional committee. Right: Commander Scott D. Altman, left, assists Pilot Gregory C. Johnson during a computer-based landing simulation.

The next day, their 10th in space, the astronauts had most of the day off, having accomplished their mission to refurbish the Hubble Space Telescope. They took the traditional in-orbit crew photographs, held a press conference with reporters around the world, spoke with the Expedition 19 crew aboard the space station, and took a congratulatory call from President Barack H. Obama. After reviewing the late inspection imagery, Mission Control formally cleared Atlantis for entry and landing, planned for two days later, although meteorologists kept a wary eye on the weather forecast for Florida, advising the astronauts to conserve power in case they needed to stay in orbit a little longer. The following day, in preparation for landing, Altman, Johnson, and McArthur tested Atlantis’ auxiliary power units, reaction control system thrusters, and flight control surfaces, and the entire crew began stowing items no longer needed in the cabin. Altman and Johnson practiced landing the shuttle using a laptop based simulator. For the first time in history, the entire crew testified before a congressional committee. Senator Barbara Mikulski of Maryland, Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies, and Senator C. William “Bill” Nelson of Florida spoke with the crew about the importance of spaceflight in general and the repair of Hubble in particular. The STS-125 astronauts held another news conference, primarily with domestic media. Based on the results of the late inspection that showed no damage to Atlantis’ heat shield, Mission Control officially released Endeavour from its standby role as a rescue vehicle, allowing workers to begin preparing it for its next mission, STS-127.

Left: The San Francisco and Monterey area in California. Middle: The western half of the Houston metropolitan area. Right: The Cape Canaveral area in Florida.

Weather in Florida did not cooperate with the STS-125 astronauts on May 22, their 12th and planned landing day. Mission Control passed on both landing opportunities at KSC, advising the crew to stay in orbit one more day, and called up Edwards Air Force Base as a backup site for the next day, providing six landing opportunities, three at each site. On Flight Day 13, Mission Control passed on all the opportunities, but with a strong desire to bring Atlantis home to KSC, extended the mission one more day, hoping for better weather in Florida. The astronauts meanwhile added to their already rich store of photographs of planet Earth.

Left: Atlantis lands at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Middle: The STS-125 crew poses in front of Atlantis at Edwards after their successful mission. Right: Atlantis atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft during its return to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

With two opportunities at each landing site on May 24, Mission Control concluded Florida’s dynamic weather as unsuitable and elected to bring Atlantis home to California. The astronauts donned their LESs and prepared for the return to Earth. They closed the payload bay doors and fired Atlantis’ OMS engines to bring them out of orbit. Just before landing, Johnson lowered the craft’s landing gear and Altman guided Atlantis to a smooth touchdown on concrete runway 22, concluding a flight of 12 days, 21 hours, 37 minutes. They circled the Earth 197 times. It marked the last landing at Edwards for Atlantis.

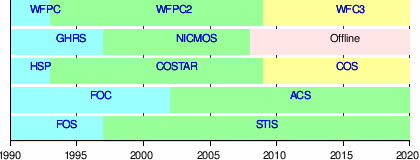

Timeline of the Hubble Space Telescope’s instruments and their replacements during servicing missions.

The STS-125 crew’s work left the Hubble Space Telescope in its best condition ever, carrying a suite of instruments far more advanced than its original complement. As it continues to operate, Hubble far exceeded the five-year extension their servicing mission expected to provide. The repairs and upgrades to the Hubble Space Telescope enabled it to continue operating until the James Webb Space Telescope joined it in space in 2021. The two telescopes together give astronomers the ability to study the universe from the ultraviolet through visible light and into the infrared range of the electromagnetic spectrum. During the five servicing missions between 1993 and 2009, 16 spacewalking astronauts conducted 23 spacewalks totaling more than 165 hours, or just under 7 days, to make repairs and improvements to the telescope’s capabilities. To summarize the discoveries made by scientists using data from the Hubble Space Telescope reaches well beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that during its more than 30 years of operation, information and images returned by Hubble continue to revolutionize astronomy, literally causing scientists to rewrite textbooks, and have dramatically altered how the public views the wonders of the universe. On the technical side, the launch of Hubble and the servicing missions to maintain and upgrade its capabilities have proven conclusively the value of maintainability of space-based scientific platforms. Although the now-retired space shuttle provided a unique platform to service Hubble, astronauts during STS-125 attached a soft capture mechanism, holding out the possibility of future servicing missions by other vehicles.

Watch the STS-125 crew narrate a video of their Hubble servicing mission.